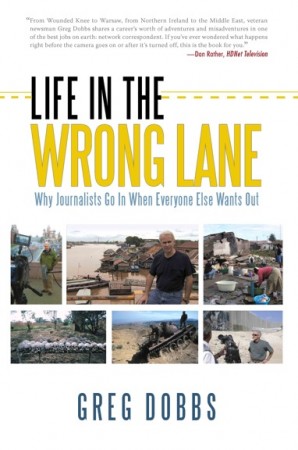

Life in the Wrong Lane

The Night I Surrendered to a Cow

The first sign was maybe a hundred yards ahead of us, at the top of a hill, silhouetted in the dark night. A lone figure, erect, like a statue at the top of a treeless slope, the barrel of his rifle standing out against the night sky. He seemed to be peering right down at us. If he was a fed, he was just waiting to clamp on the cuffs.

We stopped short and whispered to each other. Fed, or Indian, or angry rancher? No way to know. But it didn’t really matter. Whoever he was, he wasn’t acting real friendly.

We could cut fast to the left or right and hope to outrun him. We were weighted down with tens of thousands of dollars in camera equipment, but who knows? Maybe in this deep snow, we could move just as fast as he could.

And maybe we couldn’t. Furthermore, outrunning him might not be our biggest challenge. What if he shoots at us? Could we outrun the bullet?

So we decided to surrender. After all, if he was an Indian, he’d probably help lead us back to Wounded Knee. If he was a rancher, he’d probably read us the riot act and tell us to get the hell off his land. And if he was a fed, well, we were just journalists. Sure, we were trespassing, and sure, we had illegally crossed a government barrier, but if this was an agent, what would the government do to us except slap our hands and send us home?

“We’re journalists and we’re not armed.” I tried to keep my voice calm as we took maybe a dozen steps in his direction. But he was calmer than I was; he hardly moved. And he didn’t say a single word back to us. So now, Art spoke.

“I’m Art Levy. I’m a cameraman for TVN. My partner is Greg Dobbs. He’s a producer for ABC.” And with that, we took another dozen steps toward our captor.

But he didn’t respond. Or move. We could still make out the shape of the rifle’s barrel.

“We’ll put our hands in the air, just to show you we mean no harm.” Art seemed to have the right idea now. Just as we could only see this guy in silhouette, maybe that’s how he saw us. And all our protruding equipment, which just as easily could have looked to him like weapons as TV gear. Picture me, walking along with this long tripod sticking out front. In the darkness of the night, it looks like a long gun. “Just give us a few seconds to put all our equipment down.”

We set everything down in the snow. That should reassure him. And we put our arms in the air. That should too. And we took a few more steps. He didn’t take even one. This was beginning to worry us. It’s bad enough to get arrested. Worse still to be captured by some nut with other things in mind. But that was how it seemed to be shaping up.

“Look.” My turn again. “We’re going to keep coming toward you, slowly, unless you tell us to stop. And we’ll keep our arms in the air. But we want you to see us, and we want to show you our press credentials, and show you that we don’t have any weapons.”

He didn’t say not to, so we began stepping through the deep snow. One tall step after another, closer and closer to the mysteriously still and silent figure. Remember, it’s a dark night. We’d have to be nearly nose-to-nose to make out more than just his shape.

Which is what it took. It wasn’t until Art and I were just a couple of yards from this stoic figure that we could see that he wasn’t an Indian. Or a rancher. Or a federal agent.

This guy had four legs. We were surrendering to a Black Angus bull. With a long horn that stood out above his head like a rifle.

We were so shaken, we apologized.

Champagne From A Styrofoam Cup

The Ayatollah’s aides—the president destined to be exiled, the foreign minister destined to be executed—had promised me an interview with Khomeini. So I went with a crew and a translator—Behray Taidi, an out of work English-speaking Iranian TV cameraman whom we had hired to work with us—to the elementary school in Tehran that had been Khomeini’s headquarters since he returned in triumph.

The schoolyard, surrounded by a chain link fence, was packed with people. Khomeini’s entourage had announced that he would hold a public audience. What that meant was, he’d stand at a window and weakly wave his hand at the masses.

We pushed our way in. The pictures would be great.

Bad decision. Once we were in, we couldn’t get back out. And with more people pushing in, neither could anyone else. It wasn’t like squeezing ten pounds into a five-pound bag. It was like squeezing a hundred pounds into the bag.

By the time we were near the Ayatollah, we couldn’t move. Not under our own power anyway. The crush was so tight that we, like everyone else, got picked up and carried by the human tide. If your arm was down at your side, you couldn’t lift it. If it was up in the air, you couldn’t bring it down.

Behray had a Rolex wristwatch. It came off. There was nothing he could do. To try to reach for it on the ground would have doomed him to death by crushing. Several people did die that day in the schoolyard.

Ironically, we have the Ayatollah himself to thank for our lives. Standing at the corner window, weakly waving his hand at his subjects who were pinned in too tight to wave back, he saw us in the crush and signaled to his aides. They nudged Khomeini away from the window and reached out for us, pulling us one by one across the windowsill and into the room. Ayatollah Khomeini. What a guy.

I Was Only Driving An Ambulance On The Russian Front

Just as quickly as my contact had appeared out of nowhere, two more guys did the same. But they didn’t sit down at the table. They towered over it.

My tablemate started shaking. Not a single word from our visitors, but he seemed to know who they were and why they were there, and he was shaking, and starting to mutter, and then squeal, “No, not me, no, not me, nooo …”

It didn’t really seem like a party where I wanted to stay. But it didn’t seem like I could just get up and leave, either.

It felt like they stood there for a minute or so, just staring down at this guy next to me. But there was a message in their eyes: “Come peacefully, or not. Up to you.”

Not.

I don’t think the shaking man at my side actually made some kind of conscious decision to hold his ground. I think he was just too scared to move. So they moved first. These two thugs reached over the table, each grabbing this guy under one arm, and pulled him across. Coffee cups and cream and sugar bowls went flying, but hey, the owner can always buy more.

My contact wasn’t just squealing anymore, he was screaming. “Noo, nooo, pleeeese, noooo, nooooo, noooooo!”

Three things flew through my mind: 1) Live by the sword, die by the sword; 2) Maybe instead of journalism school, I should have gone to law school; 3) I was real glad I never learned the guy’s name.

Now let me tell you what happened with our eyes: mine never met his. The abductors were bad guys, but he was too, and I didn’t want any part of his problem.

And their eyes never met mine. They were about as interested in me as they were in the porcelain now shattered on the floor. Thank goodness!

The other customers, veterans of life in Beirut, never looked up. Well, maybe once, but then they quickly resumed the appearance of non-involvement that had kept them alive so far through all the years of Lebanon’s civil war.

That was the last time I saw the guy who sent me a message to meet him at the Alexander. The last time I even heard about him. His abductors had to drag him, kicking uselessly, all the way to a car. My hearing’s not so hot, but I could hear him screaming ’til they slammed the door on their way out. I don’t suppose he screamed much longer.

That might have been the end of it. But I couldn’t be sure. Some mysterious American arms dealer had just been dragged kicking and screaming from a hotel coffee shop by a couple of mysterious Arab thugs, and I was the other guy at the table. Worse still, he had left the briefcase.

Life in the Wrong Lane by Greg Dobbs

ORDER NOW!

Order Information

Greg’s book sells for $13.95 and is available at iUniverse.com, BarnesandNoble.com and Amazon.com.

It would make a great Christmas gift for any news junkie on your list!